I’m not going to sit here and splutter out some vapid phrase like “wow, a game that actually feels like being in a war!” I’m one of those incredibly lucky people who has never known war. I’ve felt the shadow of conflict creep into ordinary life on several occasions. Be it Ireland’s far reaching consequences from its history of conflict, the 2004 Madrid train bombings when I lived in Spain, or the fact that the UK government keeps insisting I should be really scared of the extremists, who are apparently one step away from hiding under my bed at night. War has never torn through my street, blown the roof off my house and made me flee with bullets cracking at my heels. I do not know what it is like to go hungry, to seek safe shelter, or to live with chaos threatening to blow your life apart without hesitation, day in and day out. While millions of people the world over face this cold reality, I do not. I’m lucky.

My picture of war is a patchwork of the media I consume and rather a few years studying various conflicts. Games really like war. They offer up exciting scenarios in which the player can enact ever more heroic deeds. This War Of Mine is quite unlike any war game that has come before it. It is the antithesis of the big blockbuster action game. It doesn’t cast you as a super-soldier. You do not take down any dictators with a rag tag group of rebels. Your enemy is hunger and depression. Your supplies meager, your health failing. Poland is a country that has been partitioned and reconstituted, suffered through occupation and Soviet rule. It neighbours countries that have just as tumultuous histories, and it could potentially be the next big video game industry in Europe. The more I played This War of Mine, the more I was convinced a game like this could only come from a place like Poland.

The war in This War of Mine is never specified. Rebel and Government forces duke it out for control of the besieged city of Pogoren. It is a surrogate for Warsaw in 1944, Belfast in the 1970s, Sarajevo in the 90s and Damascus in 2012. The muted palette of a weary existence is brought out in stark detail with its pencil sketched style. Simple comforts like heating or coffee are not guaranteed, and your survivors scratch a paltry living together. Rummaging through piles of dirt for any supplies that might lie beneath.

During the day you must manage your team in their shelter. Search every nook for supplies, use scrap to try and make your shell of a home at least a little bit liveable. This means knocking up a few beds and chairs at your tool bench. The first thing I made was a radio so I could tune in to news bulletins. It became something of a morning ritual. I would always leave it on the classical music channel when I had heard all of the reports. I don’t know if it affected my people, but it made me feel better. Then I’d get to the task of making sure my survivors were well fed and well rested. It was easier in the beginning.

Later you can construct tools. A shovel clears piles of rubble fast. A crowbar can unblock doors or cabinets. They can also be used as weapons when you get into trouble in the skeleton of a ruined building. Under the cover of darkness you choose one survivor to go out into the city to gather supplies. The others remain, standing guard or sleeping. The night brings fear, as it is where you will face direct danger. Yet it also brings the opportunity to scrounge for food, medicine and other essential materials.

During these phases you choose a location from a map which gives a vague list of possible supplies that can be found there, along with a danger level. My first night went off without a hitch. I found food a plenty. Pavle had a large rucksack and he was a fast runner. The perfect candidate. I couldn’t have known then that it would be starvation and depression that would kill him two weeks later.

During the night you have to make effective use of your time. Up against a timer it is better to firmly know what it is your looking for going into any given location. I had thought the night would simply end when dawn came. Not so. Dawn brought its own set of dangers, and if you get caught short you return to your shelter without the person you sent out. The game informs you it will be harder to get home and avoid patrols in the light. Suddenly the tension that permeates the game was within me. Never mind my worried crew. I was worried! I had no idea when Pavle would return. I had no idea if he would ever return.

By night six I was getting the hang of things. My supply of food had run out and so I tasked Katia with investigating a supermarket. I also brought a rucksack full of things I was willing to trade. Katia’s skill was as a negotiator and I was getting desperate. What I found was a soldier conversing with a woman clearly looking for supplies, like I was. The trooper offered the woman food in exchange for sexual favours. She refused, but it became increasingly apparent he wasn’t going to take no for an answer.

In one of the few overtly heroic acts I engaged in, I managed to sneak up behind him and beat him with my shovel. He seemed unwilling to shoot me, but that didn’t stop him from raining a few vicious blows into Katia’s face with the butt of his rifle. After the struggle the soldier was dead, the woman had disappeared and Katia was severely wounded. I now had a rifle, but the supermarket turned up zero food and Katia would now need the last of our medical supplies if she was to survive the coming days.

It’s easy to think that this game would only pile on the negativity day after day, forcing your hand to take more drastic action. You’d be right, it certainly does. It also acknowledges that not everyone you meet is a monster. I found that people rarely shot on sight, though I took no chances with the psycho who stalked a hotel. People will often be willing to barter. If other survivors turned up at my shelter I offered them my hospitality.

It was how I met Zlata. She was a blessing in disguise, whose skill was raising the others spirits. It meant I didn’t have to let Katia guzzle down alcohol in her depression after having taken a life through such violent means. While Bruno, our cook, only looked out for his group, I regularly had Pavle spend the day helping neighbours, occasionally returning with payments for a job well done.

Had the game ignored these aspects, the overly pessimistic view may have made the experience ring hollow. However by allowing these brief glimpses of humanity and cooperation it offers up a relatively nuanced look at the many ways people act when under duress. Early on I went to what was marked as the Quiet House. Again my food had ran out. Inside I found an elderly couple. The old man pleaded with me not to hurt his sick wife. Before I knew it they were cowering upstairs and I’d robbed them blind. I tried to justify it, but that night I turned the game off and went to bed feeling genuinely awful. I never did return to that house days later. I didn’t want to face the consequences of my actions.

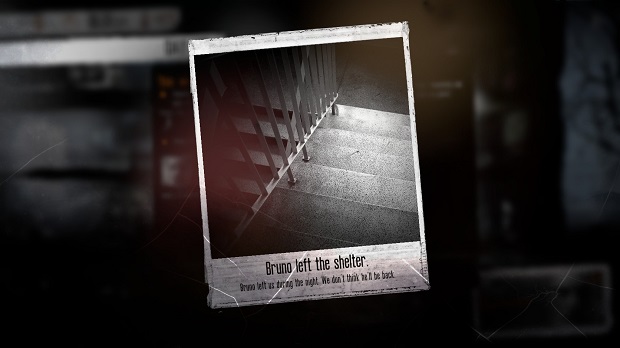

My war lasted 16 days. Katia died on a supply run before she could even get a shot off with the Kalashnikov. She never really recovered from her run in with the soldier. Zlata succumbed to wounds defending the shelter from raiders. Utterly depressed Bruno left during the night. The epilogue tells me a patrol killed him when he tried to make his way to a friend. Alone, depressed, wounded and starving, Pavle could only lie on his dirty mattress in a pit of despair.

I cannot say whether This War of Mine is an accurate portrayal of life in a war zone. I have no point of reference to do so within my own life. It is a game of stark and often swift brutality. The first gunshot you hear will undoubtedly send a cold chill down your spine as you pray you don’t run into any armed bandits. It is also a game about survival, companionship and ultimately hope. One day the war will end, and just maybe you’ll be around to see it, and begin to pick up the shattered remains of your life.

When video games are content to provide us with overblown power fantasies about the glory and bombast of fighting for what is right and true, here is a game that says that actually, war is really shitty. War destroys lives and kills dreams. That maybe we’re all becoming a little too desensitised to the violence on our screens. It is a game about living in the moment, and living with the consequences of your actions.

This War of Mine is a very good game in and of itself. More than that, it is an important video game. One that needed to be made.

As the wind rattled through the empty house, the stove no longer spilling heat and static on the radio, I wonder if Pavle thought about that old couple he robbed, as he slipped noiselessly off his mortal coil. To join those who had gone before him.

This War of Mine was reviewed using code provided by the developer.